Cultural theorist and historian Aby Warburg (1866-1929) used to say that God is in the detail: der liebe Gott steckt im Detail. This phrase expressed a sort of methodological credo for Warburg and the school of cultural historians which formed in the library he founded: namely, that it is through the attention to, identification and observation of the telling detail that truths about human history may be uncovered. For the Warburg School, human history and the history of culture were almost interchangeable concepts. According to the Warburgian philosopher Ernst Cassirer, “culture” could be understood as the home the human mind makes in nature, and thus the history of culture (which is a history of forms) is the history of humanity’s homemaking in the universe.

This philosophy of detail, however, was not an idiosyncratic insight unique to Warburg or even to his school. Rather, it is itself a detail out of which a culture and a history may be extrapolated. What we may term ‘detail orientation’ is a (perhaps the) key characteristic of humanist culture.

Humanism in this sense is a culture centered on the study and practice of the so-called language arts of grammar, rhetoric and logic. Grammar is the fundamental science for humanism: the study of the parts and inner workings of human language. In the Western tradition, the “dead” languages of Greek and Latin take precedence because on the one hand their grammar was thoroughly theorized in Antiquity, and on the other they provide in their fossilized state a perennial and for all intents and purposes an unchanging common ground (an essential prerequisite for any shared concept of truth). In rhetoric (the science of persuasive language) we find ultimately the roots of all the genres we associate with literature in its broadest sense: language intentionally wrought, whether into a speech, a poem, a detective novel, a work of historiography, a sensationalist newspaper article, and so on. Logic in turn is the science of meaning, or of meaningful propositions, and the ways in which these may be combined and elaborated.

An intellectual praxis which weaves and blends all three together with a historical consciousness of change can be described as philological. Detail orientation is preeminently modelled for us in philology, in which tiny details of style, vocabulary, spelling, and even sometimes of the ways individual letters are drawn, help the reader place a text in its historical cultural context. Doing so is the first step towards unlocking the full potential of a textual artefact to mean. Historicizing a text does not preclude its capacity to speak to us in the present; rather, it is like replacing a monophonic recording with stereo sound. Philology thus understood appears to have been practised in Classical Antiquity, but was forgotten during the Middle Ages. The culture of the Middle Ages, so thoroughly Christian-centric, may oddly enough be described as humanist in that of preeminent importance was the textual corpus consisting of Scripture and the many works of commentary on it. But because the Biblical text was not historicized (in other words, it was believed to be transcendental and eternally and universally valid), the medievals had no use for philology. With the rediscovery of the Latin classics in the Renaissance, however, such precise attention to language came to be viewed as necessary again, initially in order to explain the striking discrepancy between the eloquence of Ciceronian Latin on the one hand and the jargon of Scholastic Latin on the other.

The story of Renaissance philology and the humanist culture it fed may indeed be told as the story of closely observed details. In the fourteenth century, the poet Petrarch noticed that the written Latin of his contemporaries had declined tremendously in elegance in comparison with the “Golden Age” Latin of Cicero. In the fifteenth century, a scholar named Lorenzo Valla brought a finely tuned attention to detail to the text of the so-called Donation of Constantine, and exposed it as a forgery, thereby dealing a blow to Papal claims to temporal authority. In sixteenth-century France, a jurist and historian, Etienne Pasquier, wrote that even the smallest changes in the usage and the forms of words could contain within them the evidence of empires.

From these examples (which could easily be multiplied) we see that a humanistically trained attention to detail in the early modern period was fundamentally comparatist: a critical gaze constantly oscillating between past and present. What we might call the value orientation of this gaze would itself oscillate over subsequent centuries, favoring sometimes the old over the new (tradition over innovation) and sometimes the opposite - originality and achievement over imitation. But in general, after the Renaissance, in a humanist culture past and present would exist simultaneously in an uneasy, unresolved, and incredibly productive tension.

The hallmark attention to detail of the Renaissance humanists would ultimately reach far beyond the written word. The relationship between humanism and the emergence of modern science in the early modern period is a difficult and fascinating one, and what is certain is that it was not a history of simple replacement or progressive succession. The “science” or “scientific worldview” of a Copernicus, a Galileo, a Descartes, a Newton did not replace “the humanities”, but was rather nurtured by and in a pedagogical culture of detail orientation rooted in the rudiments of historicized grammatical analysis. The medieval idea of the world as a book was still current in the early modern period (c.1500s-1700s) and certainly inspired those whom we look on today as the scientists of that time. If for the medievals the book of nature had been written in the Latin of the Vulgate, for the “natural philosophers” of the 1600s onwards the book of nature spoke a different language, but a language nonetheless: that of mathematics. Conjecture and comprehension, key tasks of the humanities scholar faced with an arcane manuscript, became the moves of the scientist grappling with the book of nature. And the idea of mathematics as the language of nature is not mere imagery. There is a sense in which mathematics was (and perhaps is, I don’t know) written and practiced almost like a literary language, replete with idioms and redolent with style. In one episode from the early modern history of science, an anonymous proof submitted to a competition was identified as belonging to Newton on stylistic grounds: one could “recognize the lion from his claw”, in the words of the Swiss mathematician Johann Bernoulli.

All this is to say that the sciences and the humanities as they exist today side by side in the modern university are not two different worldviews, as they are so often framed, but sibling enterprises. We might say that in their shared quest for meaning, both privilege detail over data.

In a discussion about the different meaning of the word information in an interpersonal context and in relation to computer science, philosopher Roger Scruton points out in The Soul of the World (2014) that the information we communicate between ourselves about the world is always information that something is the case, information about something. “Information, in this sense, is an intentional concept, which describes states that can be identified only through their content.” (p. 57) In a computer science context, however, “information means the accumulated instructions for taking this or that exit from a binary pathway” (ibid.), and is therefore not (strictly speaking) about anything. This, to me, seems like a useful way of thinking about data. Data of course emerge from contexts, but data are more of a radical abstraction of informational contexts than an informative description of them. The power of data lies precisely in the leverage which abstraction affords. Data are information points decoupled from their immediate contexts of meaning, information devoid of detail. Data are not about anything, but claim to represent the thing in itself in an essential, algorithmically parsable form. If detail is the preserve of the humanities and the pure sciences to which they gave rise, then data may be said to belong to an applied field which we can term “technics”. Technics is an extremely abstract field, which unlike the humanities or the natural sciences does not investigate reality but seeks to replicate parts of it in simplified and controllable imitations or approximations, from simple mechanics to computational models and fiat currency.

Technics results in the creation of tools, which may usefully be defined as “externalizations of originally integral functions […]: Tools do not introduce new principles but they greatly extend the range of conditions under which the discovered control principle may be effectively employed[.]” (Buckminster Fuller, Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth, 1969). Fuller argues that when humans discover certain principles through their investigations of reality they often develop technologies which specialize in or embody those principles, which can then be left to work with ever greater degrees of autonomy. Technics is thus a way of integrating our intellectual discoveries (Fuller calls them metaphysical discoveries) into our physical reality. I suggest that “datafication” is the defining tool of our moment: a tool for turning meaning into money.

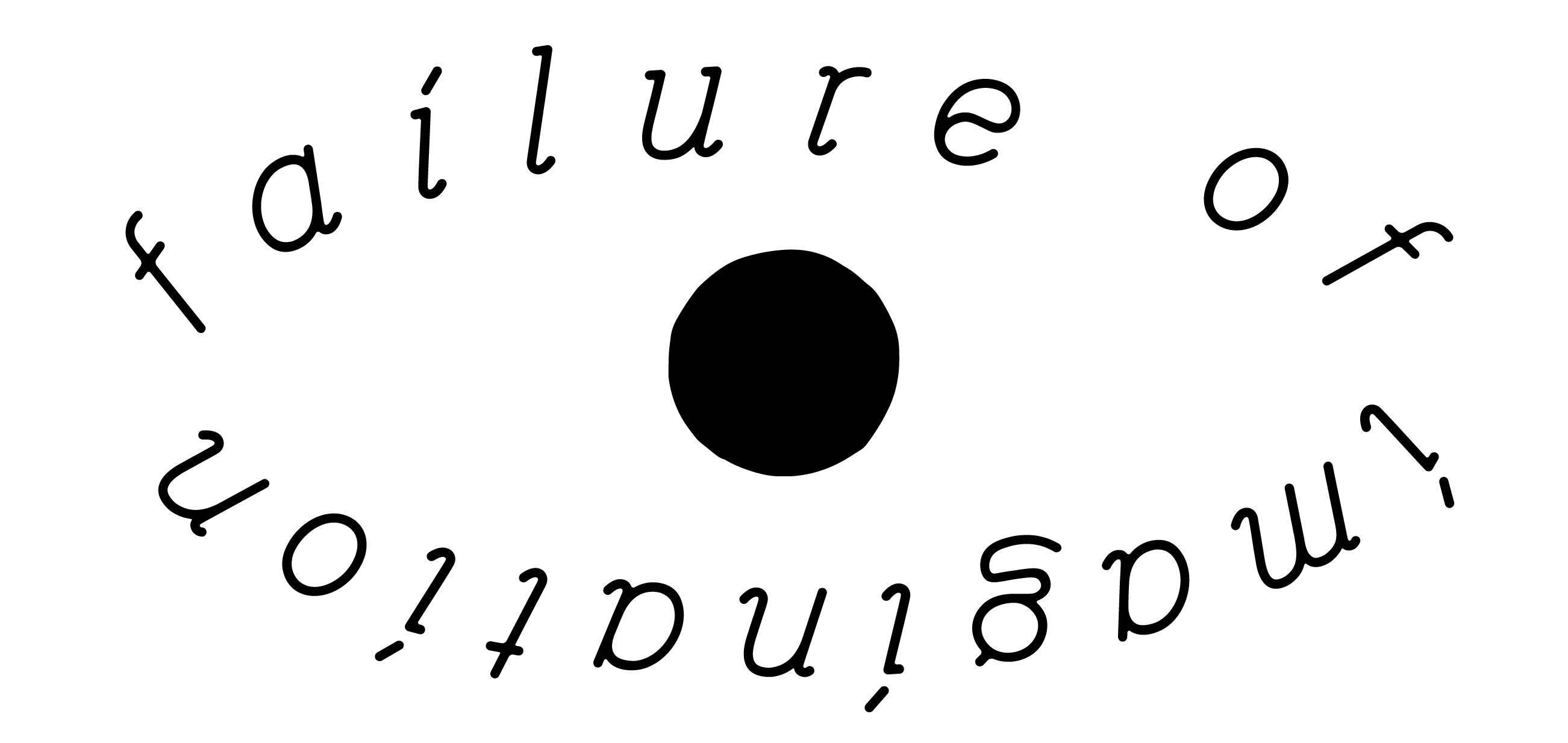

Society today is under the sway of a harsh technics. Global finance and the “tech” industry are reducing to data the world in its every meaningful detail. This economy of datafication has its infrastructure of banks and farms through which the shared meaning of our lives is systematically transmuted into unshared money. We are becoming cognizant of a choice: between making money, or making meaning. The supreme irony is that those who profit financially from the datafication of our world will not be exempt from decontextualization and the loss of meaning. In the last analysis, the billionaire will stand alone upon a mountain of money, with nothing and no-one to spend it on or with. It behooves us all to attend to the details of the world around us, to demand detail of those who speak only of data, and to fight the slide into meaningless nothing which a “data-driven” world would mean.